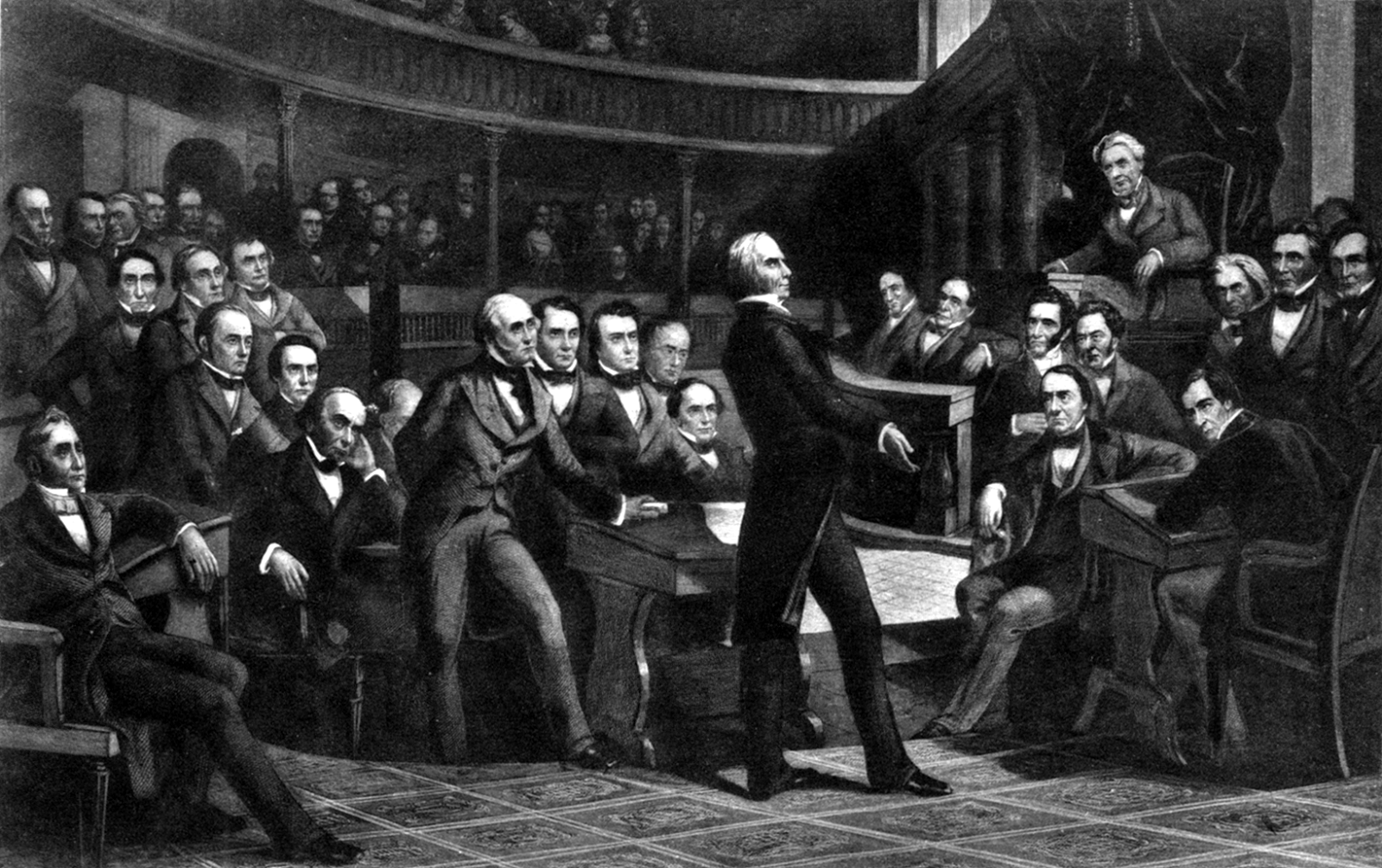

Henry Clay presents an embody bill on subjection to US Senate

ON 29TH JANUARY 1850 - Henry Clay presents an embody bill on subjection to US Senate

The Compromise of 1850 comprises of five laws passed in September of 1850 that managed the issue of subjugation. In 1849 California asked for authorization to enter the Union as a free state, conceivably annoying the harmony between the free and slave states in the U.s. Senate. Congressperson Henry Clay presented a progression of resolutions on January 29, 1850, trying to look for a trade off and turn away an emergency in the middle of North and South. As a feature of the Compromise of 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act was altered and the slave exchange Washington, D.c., was canceled. Besides, California entered the Union as a free state and a regional government was made in Utah. Additionally, a demonstration was passed settling a limit debate in the middle of Texas and New Mexico that likewise settled a regional government in New Mexico.

On January 29, 1850, Henry Clay climbed in the Old Senate Chamber to start the most essential open deliberation of his profession and to manufacture one final trade off. A Whig from Kentucky, the "Extraordinary Compromiser" entered the Senate in 1806, served discontinuously in excess of four decades, and turned into a star of the Senate's "brilliant age." He surrendered in 1842 to run for president yet returned in 1849 to look for a trade off answer for the country's becoming sectional strife—to dodge common war.

The Compromise of 1850 was a gathering of Congressional enactment proposed by Kentucky Senator Henry Clay to purpose sectional issues in the United States in regards to subjugation after the Mexican-American War. Following nine months of warmed civil argument all through the nation, Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas shepherded Clay's trade off recommendations through Congress and secured the sanctioning of enactment that: 1. admitted California to the Union as a free express, 2. Approved the regional assemblies of New Mexico and Utah to focus the status of bondage inside their fringes, 3. settled a limit question in the middle of Texas and the United States for the U.s., in return for Federal supposition of $10 million of Texas obligation, 4. abolished the slave exchange, however not servitude, in the District of Columbia, and 5. approved a more stringent criminal slave law to help guarantee the reappearance of runaway slaves. Albeit hailed by conservatives at the time as a "last settlement" to the sectional contrasts the tormented the country, the bargain enactment immediately disentangled. Just after ten years, the country was occupied with common war to focus the eventual fate of the Union, and in addition bondage in the United States.

Demonstrating the impacts of age and tuberculosis, the 72-year-old statesman proposed eight resolutions to settle the disagreement about regions procured from the Mexican War. The key issue, obviously, was whether states cut out of those domains would permit or deny subjection. As Clay clarified, he proposed a "friendly game plan of all inquiries in debate between the free and slave States." Adding show to the event, Clay created a bizarre prop. He had as of late required the national government to purchase George Washington's Mount Vernon domain. In appreciation, a supporter gave Clay a piece of wood from Washington's box. Is it accurate to say that it was ominous that this article had been displayed to him, Clay asked? Is it accurate to say that it was a sign that the country established by Washington was biting the dust? "No, sir, no," thundered Clay, holding up the relic. "It was a cautioning voice, originating from the grave to the Congress ... to be careful, to stop, to reflect before they give themselves to any reasons which might annihilate the Union."

For six long months, Clay drove the combative level headed discussion. Mississippi Senator Henry Foote recommended joining the resolutions into a solitary bill, which Clay alluded to as a "kind of omnibus" into which Foote presented "different varieties of things and each sort of traveler." The thought grabbed hold, and Clay supported the Senate's first "omnibus bill." He broadcasted it to be "not southern or northern. It is equivalent; it is reasonable; it is a bargain." On July 22, Clay conveyed his last significant discourse in the Senate, calling for section of the omnibus bill. In the event that passed, the North would pick up California as a free state and an end to the slave exchange Washington, DC, while the South would get a stronger outlaw slave law and the likelihood of western bondage through prevalent sway. This bargain, Clay demanded, spoke to the "gathering of [the] Union."

After one week, the Senate rejected Clay's proposal. "The omnibus is upset," cried adversaries. The omnibus method had fizzled as opposed to hardening help, it brought together restriction. Southerners challenged any limitation on servitude, and northerners raged at the thought of returning outlaw slaves. A crippled Henry Clay headed north to restore his fizzling wellbeing.

The omnibus bill kicked the bucket, however Clay's Compromise of 1850 survived. The reason was embraced by Stephen Douglas of Illinois, who dismantled the omnibus and repackaged it into five different bills, winning authorization of each one noteworthy procurement. Mud's last bargain served to fight off common war for an alternate decade. At the point when the Old Kentuckian passed on in 1852, he went to his grave accepting his trade off had spared the Union.

By 1850 sectional differences focusing on servitude were straining the obligations of union between the North and South. These strains got to be particularly intense when Congress started to consider whether western grounds procured after the Mexican War would allow servitude. In 1849 California asked for consent to enter the Union as a free state. Adding all the more free state legislators to Congress would pulverize the harmony in the middle of slave and free expresses that had existed subsequent to the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

Since everybody looked to the Senate to defuse the developing emergency, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky proposed a progression of resolutions intended to "Conform genially all current inquiries of contention . . . emerging out of the establishment of subjection." Clay endeavored to edge his trade off so that broad

After war with Mexico added new territories to the Southwest, the issue of slavery’s expansion gained renewed urgency. Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky championed a series of compromise measures in an effort to heal the growing rift between the northern and southern states. Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts spoke eloquently in defense of the compromise, while Senator John Calhoun of South Carolina opposed the plan. With the guidance of Stephen Douglas of Illinois, Congress eventually passed revised versions of Clay’s proposed bills, known collectively as the Compromise of 1850. The Compromise admitted California to the Union as a free state, allowed the territories of New Mexico and Utah to decide the slavery issue for themselves, and settled a Texas boundary and debt issue. While it abolished slave trade in the District of Columbia, it strengthened the existing Fugitive Slave Law by requiring free states to return escaped slaves to their owners.

Comments

Post a Comment